Home

Home

The Landscape

The 2,944 acres of Saint John’s landscape is defined by terminal end moraines – rolling hills of rock and soil that were shaped by the advance and retreat of glaciers 10,000-30,000 years ago. Saint John’s stands in a thin band of predominantly hardwood forest that runs from the northwest to the southeast corners of Minnesota. Prairie and farmland stretch to the south and west, while coniferous forest, bogs and swamps appear to the north and east.

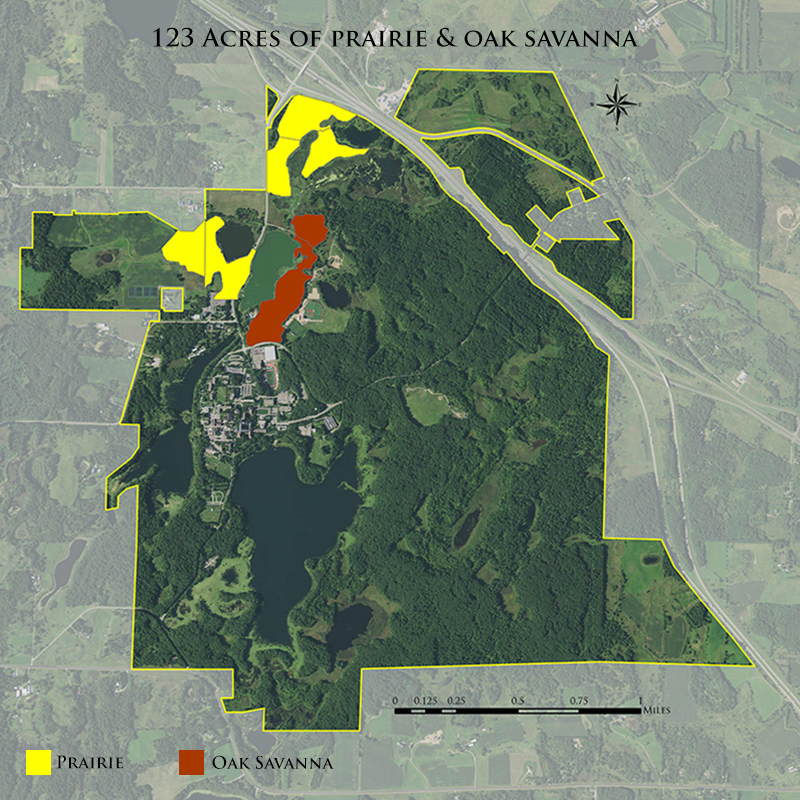

Prairie & Oak Savanna

Prairie and oak savanna are rare today in Minnesota – only about 1% of original prairie and 0.1% of original oak savanna remain. The prairie and oak savanna of the Abbey Arboretum are “constructed” and restored. According to historical records, when the Benedictines arrived the closest prairies were in Avon and St. Joseph. In the mid-1980s, Fr. Paul Schwietz began making plans to convert old cow pastures and farm fields to wetlands, prairie and savanna. This Habitat Restoration Project has resulted in about 150 acres of a healthy prairie, oak savanna and wetland ecosystem.

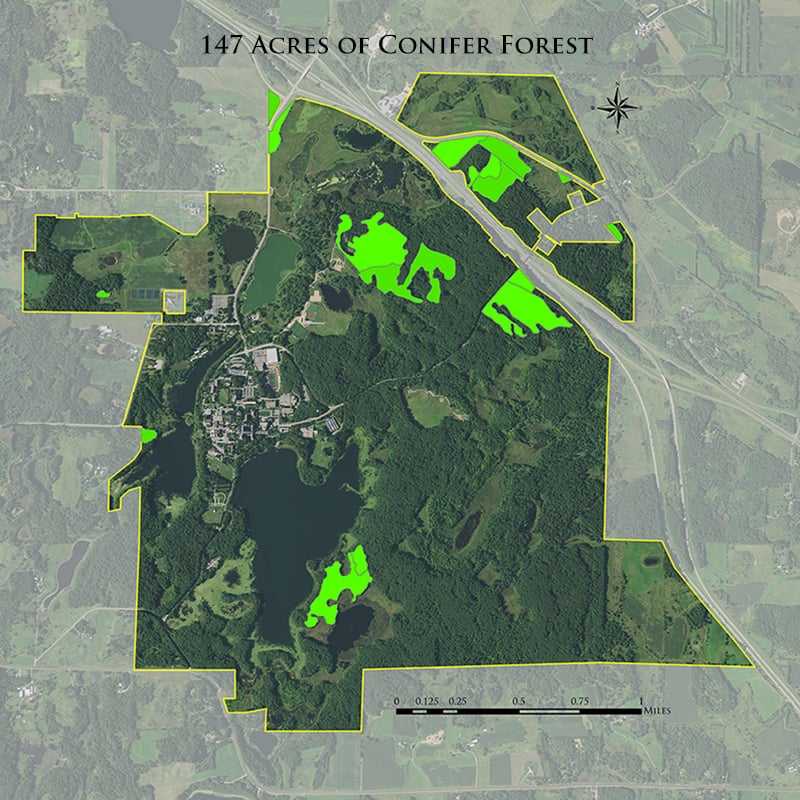

The Pines of Saint John’s

Most of the pines and conifers you see at Saint John’s today were planted by the early Benedictines. On June 27, 1894 a tornado tore across Lake Sagatagan leveling several buildings and a forest area where the prep school now stands. Fr. Adrian Schmitt, a descendant of foresters from the Black Forest in Baden, Germany, wrote to his forester father and brothers who then sent him conifer seeds by sailing ship. Fr. Adrian established a nursery of thousands of seedlings by Stumpf Lake. The first seedlings – red pine, Scots pine, and Norway spruce – were planted beginning in 1896 on 10 acres near today’s prep school and on what is now known as the Pine Knob. More plantings were completed in 1906, 1911, 1920, 1927, and throughout the 1930s. The trees grown from Fr. Adrian Schmitt’s seedlings are believed to be the oldest documented reforest planting in Minnesota. Many of the pines now bordering I-94, the Old Entrance Road, and the area around Stella Maris Chapel were planted in 1926-27 by Br. Ansgar Niess. The conifers grew fast and reminded the Benedictines of their homeland in Bavaria and Austria. One hundred years later, these pines are an iconic and familiar part of the Saint John’s landscape.

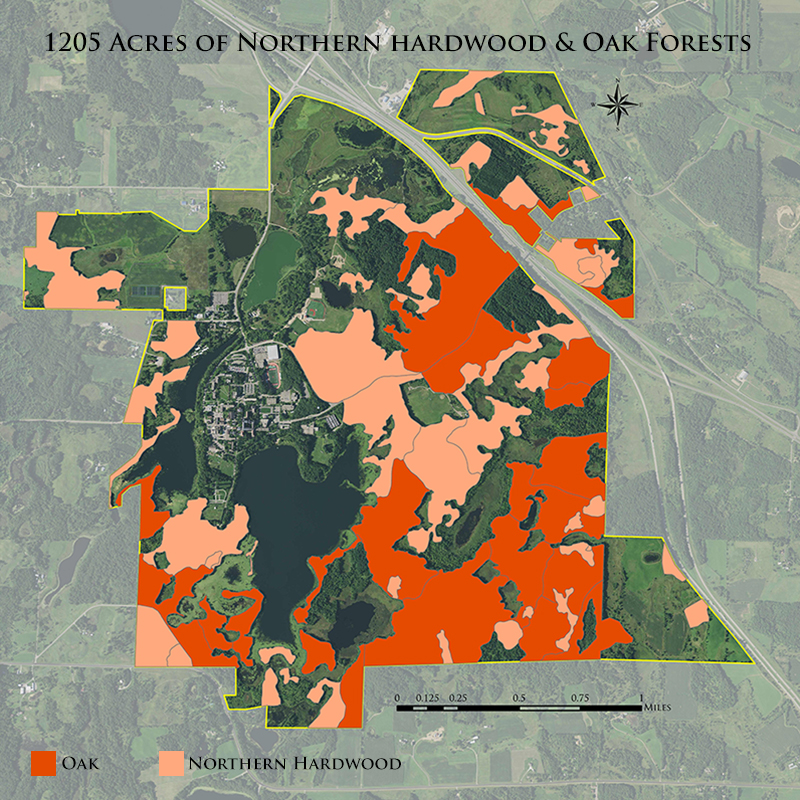

Hardwood & Oak Forests

A working woodland, the thoughtful regeneration of high-quality hardwoods such as oak is a Saint John’s priority. Red and white oak are still used to build furniture seen around campus. Oak also provides mast, or acorns, to sustain deer, squirrels and other animals. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources designates most of Saint John’s oak and maple-basswood forest as sites of outstanding biological significance.

Saint John’s was built in a mature forest of northern hardwood and oak, a habitat that has grown rare in the region. Without regular disturbances such as fire, blowdown or intentional harvest, shade intolerant species like oaks naturally decrease in the landscape in favor of the more shade tolerant maple, basswood and aspen. Regular burning, probably by the Dakota Indians, helped maintain oak dominance prior to European settlement. The monks rapidly harvested timber for building and heat which actually helped regenerate the oak forest as more light reaching the forest floor gave rise to oak seedlings, now the towering trees we see today that are 125-150 years old. While regenerating species like maple, basswood and aspen is relatively simple and requires little effort, regenerating long-lived species like oak and pine in the presence of high populations of deer is more challenging and especially labor intensive.

In addition to oak management, Saint John’s has a 29-acre grove of about 1,500 mature sugar maples, managed for the Saint John’s Maple Syrup operation. Prompted by sugar shortages during World War II, the monks started making maple syrup in 1942, making Saint John’s one of Minnesota’s oldest maple syrup operations.

Lakes & Wetlands

There are over 500 acres of surface water within the Abbey Arboretum, 200 of which are wetlands. Three of the most visible lakes are actually part of the North Fork of the Watab River, which begins upstream from Stumpf Lake, and has been dammed several times since the 1860s. Read more about individual lakes below.

Restored Wetlands

The surface area is 42 acres. These manmade wetlands were created as part of the Habitat Restoration Project by Fr. Paul Schwietz along with 150-acres of surrounding prairie and oak savanna in the late 1980s, following the original course of the Watab River which continues under I-94 towards the Mississippi River. The wetlands provide diverse wildlife habitat and allow for filtration of water. Water levels can be adjusted seasonally to attract wildlife – higher water in spring for waterfowl nesting and lower water in late summer to provide mud flats for seasonal bird migrations. Wimmer Pond is hydrologically connected to the wetlands.

West Gemini Lake & Steinbach Creek

The surface area of West Gemini Lake is 12 acres. It was originally a wetland prior to damming of the Watab River. Steinbach (German for stony brook) creek originates in undeveloped, forested wetlands less than a mile west of West Gemini. The Gemini lakes are connected by an equalizer pipe under County Rd. 159.

East Gemini Lake

The surface area is 37 acres with a maximum depth of 11 feet and a mean depth of 5.5 feet. East Gemini is a manmade lake that was created as a settling pond for phosphorus being released from the wastewater treatment plant. The Gemini lakes were named in the 1960s when the United Sates was conducting the Gemini manned space flights. The oak savanna surrounding the eastern half of the lake was former pasture land for the abbey and university’s cowherd.

Stumpf Lake

The surface area is 68 acres with a maximum depth of 36 feet and a mean depth of 10 feet. The name Stumpf (German for stump) was given after exposed tree stumps remained in the newly created lake behind the dam that was constructed in 1868 for a saw mill and flour (grist) mill. A culvert at the previous dam site allows water to flow to East Gemini Lake.

Lake Sagatagan

The surface area is 176 acres with a maximum depth of 40-42 feet and a mean depth of 9 feet. Lake Sagatagan is a natural kettle or pothole lake with no direct water inputs or outputs, which is uncommon for Minnesota lakes. The lake is recharged by underground springs, rain and snow from the surrounding land. The lake along with the fine timber surrounding it was the major draw for Fr. Bruno Reiss and the early settler monks. The lake was originally called Lake Saint Louis after King Louis (Ludwig) of Bavaria, an early benefactor of the Benedictines. The name was later changed to Sagatagan, an Ojibwe word meaning punk or fungus outgrowth on trees used for tinder, from its reference in an 1896 poem by Alexius Hoffman, OSB. Lake Ignatius is hydrologically part of Lake Sagatagan with a channel connecting the two.

Lake Hilary

Lake Hilary is tucked deep into the woods and was once a swamp with far less open water. The monks dammed the outlet of the swamp, initially as a way to maintain the trail. The small dam raised the water level to about 5 feet at the deepest point, but the dam eroded over time, slowly lowering the level of the lake. Lake Hilary doesn’t have any fish, but does have minnows that survive the ice that freezes to the bottom in many areas of the lake.