Bresnahan carries rich legacy of The Saint John’s Pottery into the future

September 17, 2019

By Dave DeLand

Richard Bresnahan’s family includes (from left) daughter Sarah, wife Colette, son Richard III, Bresnahan and daughter Margaret.

Upward of 50 volunteers work in shifts during the 10-day span of a Johanna Kiln firing to help produce roughly 12,000 works of pottery and sculpture. The Saint John’s Pottery was featured in producer/director John Whitehead’s 1997 documentary film Clay, Wood, Fire, Spirit: The Pottery of Richard Bresnahan, which won Emmy Awards for Best Cultural Documentary and Best Documentary Editing.

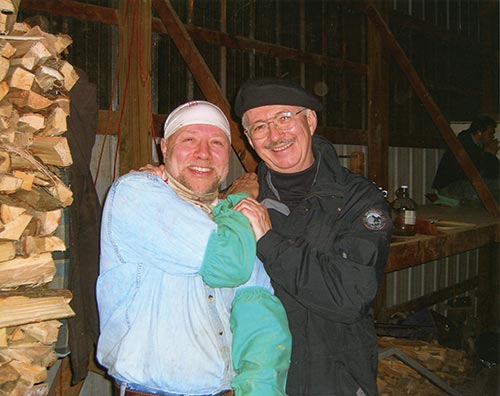

(Left) Richard Bresnahan and Saint John’s President Br. Dietrich Reinhart share a celebratory moment at the 2008 Johanna Kiln firing.

Beauty and inspiration surround Richard Bresnahan every time he unlocks the basement door at Saint Joseph Hall and walks into The Saint John’s Pottery studio, which resonates with voices from its living history and potential for the future.

Forty years. Fifteen Johanna Kiln firings. Countless lives enriched.

They’ve all blended together over four formative decades in which Saint John’s University’s artist-in-residence built something special from the ground up, literally from the clay of Central Minnesota.

“People will offer you a window,” Bresnahan said. “Br. Dietrich (Reinhart) opened up a very big window for me to walk through. Fr. Michael Blecker opened up a window of the vision for me to walk through and actualize my dreams.

“And to actualize your dreams is something that’s incredible for you to do.”

Those dreams have brought international renown to Bresnahan, to the studio and to Saint John’s.

“As both an artist and an ambassador for the natural environment, Bresnahan takes his place as one of the preeminent potters in contemporary American ceramics,” wrote Gerry Williams, editor of Studio Potter magazine.

“By his own example, Bresnahan provides his students with alternatives, showing them how to be financially independent, maintain a sense of personal integrity and create art true to themselves,” Minneapolis Institute of Art deputy director and chief curator Matthew Welch added in his landmark 2001 book "Body of Clay, Soul of Fire" that serves as the seminal chronicle of Bresnahan and The Saint John’s Pottery.

Oct. 18 will mark the 15th firing of Saint John’s Johanna Kiln, with upward of 50 volunteers working in shifts over a 10-day span to help produce roughly 12,000 works of pottery and sculpture.

It’s a process that embodies the integration of aesthetic, scientific, humanistic and moral approaches to sustainable living in relation to nature.

It’s the personification of the Benedictine values of community, hospitality, environmental stewardship, self-sufficiency and tradition.

It’s an integration of art and life, of work and worship, and a celebration of cultural diversity and how liberal arts can help save the planet.

“The impact of the studio has been really outside that narrow-siloed mainstream of art. It’s the dedication of a community for the better whole of society and the better whole of the future of education,” Bresnahan said.

“The way he lives that as almost a kind of ministry is something he and only he could have started,” said Steven Lemke ’08, a former studio program manager now studying in Slovakia on a Fulbright Fellowship. “He embodies that so thoroughly, so genuinely.”

And yet, over those four decades, other pivotal people and indelible voices have helped define the trajectory of The Saint John’s Pottery.

Foundation of a dream

Richard John Bresnahan II was born in Casselton, North Dakota, went to high school at Saint John’s Prep and graduated from Saint John’s University in 1976.

Saint John’s/College of Saint Benedict art instructor Sister Johanna Becker, OSB, helped arrange for Bresnahan to apprentice in Japan for three-and-one-half years with master potter Takashi Nakazato, whose family has crafted pottery on Kyushu Island for 15 generations.

Bresnahan lived, worked and learned in an environment that mirrored Benedictine monasticism, rich in tradition, technique and Japanese culture.

He brought those concepts back with him to Collegeville, where in February 1979 Saint John’s President Fr. Blecker agreed to help Bresnahan set up an indigenous pottery studio that would shape the future of creative education at SJU.

“He looks at me and says, ‘What can Saint John’s do for you?’ That was this incredible moment,” said Bresnahan, channeling Fr. Michael’s voice.

“I said, ‘I’d like to build a program that’s never been done in the United States.’ ”

Bresnahan became Saint John’s artist-in-residence. On June 11, 1979, The Saint John’s Pottery opened its doors.

“I wanted to build a program based on environmentalism – that we dig only our own clay, we work only out of the recycled system, we make all our own glazes,” said Bresnahan, who modeled everything after his Japanese experience.

“This was a different way of educating completely. It was taking a Pacific Rim concept and introducing that into an academic, pedagogical system. Nobody was doing this.”

Bresnahan’s initiative advanced with the help of a litany of supporters.

“There are a lot of people who are in the cemetery that went to bat for me. They didn’t have to,” he said.

“My cemetery heroes? We’ll start out with Fr. Michael Blecker. Sister Johanna Becker. Sister Colman O’Connell. Br. Hubert (Dahlheimer). Br. Dietrich Reinhart. Al Heckman.”

They also include Br. Mark Kelly, John Pellegrene and others who contributed to laying The Saint John’s Pottery’s unique foundation.

“There were only two other wood-burning kilns in the United States in 1979. Now? Thousands,” Bresnahan said.

“It’s been a cultural transformation. (Saint John’s) was at the forefront of it.”

A moving evolution

Bresnahan worked tirelessly to grow the studio during its formative years, attacking his 18-hour work days with a creative passion.

A pivotal period was 1991-92, when The Saint John’s Pottery gained an important ally and literally moved forward.

Br. Dietrich was installed as Saint John’s 11th president July 1, 1991. Bresnahan still recalls their conversation as they shook hands in the reception line at the Old Gym.

“He said, ‘Richard, we’re going to do great things together,’ ” Bresnahan said. “That moment was when I realized there was going to be a major turn.”

Br. Dietrich saw the studio as an essential element of 21st century learning at Saint John’s. He also saw the necessity of preserving its historic home: Saint Joseph Hall was facing demolition to make way for the construction of Sexton Commons.

“I was faced with tearing down Joe Hall and the choice of either getting rid of Richard or finding money to put him in a new space,” Br. Dietrich said in "Body of Clay, Soul of Fire."

He chose the latter.

“One, we’re going to lift up and move Joe Hall,” said Bresnahan, channeling Br. Dietrich’s words. “We don’t tear down our history.

“And two, we’re going to have a (monastery) chapter vote that the pottery studio of Saint John’s is part of the identity of the place – for the university and the monastery.”

The vote was overwhelmingly supportive. And in 1992, 780-ton Joe Hall was placed on 216 wheels made for Boeing 747 airliners, wheeled out onto the Tundra, turned 180 degrees and deposited in its current location 500 yards away.

The price tag for moving the building, rebuilding the studio and constructing the Johanna Kiln was formidable. To make that happen, Bresnahan went back to his family roots.

Frank Ladner ’48 was 17 when he arrived at Saint John’s in 1944. He was befriended by another Fargo native – Richard Bresnahan I ’49, just home from serving in World War II.

Ladner went on to make a fortune in the insurance business and serve on Saint John’s Board of Regents. He never forgot his roots, or Bresnahan’s father.

“I said, ‘Frank, can you help us out so that we can build a whole new program?’ He got out his checkbook, and he writes out a check for $400,000,” said Bresnahan, his voice lowering to a crackling whisper and his eyes welling with tears.

“He hands it to me and says, ‘This is for your dad.’ ”

Serving the community

The Saint John’s Pottery has continued to evolve since then, attracting visitors from around the world while enhancing artistic innovation, supporting apprenticeships and community outreach, fostering religious and academic environment and promoting natural and environmentally friendly artistry.

“Saint John’s is a community of highly diverse groups. They’re coming to learn about the culture of the clay world from this perspective. It’s a much more organic perspective,” Bresnahan said.

“The Saint John’s Pottery never has been simply about pottery,” Welch said. “It stimulates thinking, prompts psychic investment, even moves one to positive action.”

In a nationwide academic climate where many cash-strapped universities are shuttering art departments, Bresnahan has been careful to cultivate a financially self-sufficient program with a vibrantly creative legacy.

“We’re the only university in America that’s got a designated endowment for environmental artists,” said Bresnahan, ever mindful of the program’s generational survival. “The studio becomes an identity for all creativity within the university.

“Historically, what’s going to be the biggest thing 20 or 30 years out? It’s going to be environmental artists communicating about the nature of what’s happened to the planet.”

Some of those artists will be on hand for the latest firing of the Johanna Kiln, which was inaugurated in 1995. At 87 feet long with a 37-foot backpressure tunnel, it’s the largest wood-fired kiln of its kind in North America.

It’s being loaded with everything from fine art to dinner plates, which in itself makes a statement about the mission of The Saint John’s Pottery.

“If your neighbors are not eating out of your dishes,” Bresnahan said, “you have defeated the purpose of building culture.

“That’s been a main focus of the studio – it’s been more of a direction of community than it has Richard Bresnahan becoming famous.”

Looking ahead

So, what’s next?

“I wake up in the morning and I’m absolutely, totally consumed by that thought process,” said Bresnahan, who in addition to preparing for the kiln firing has been commissioned to craft the centerpiece for the Jon Hassler Sculpture Garden outside the Reinhart Learning Commons. “The feeling is you cannot wait to get to the next step of your work.”

Bresnahan recovered from major back surgery in 1988-90, and from quintuple bypass heart surgery in 2017, and has balky knees.

He couldn’t wait to get back to work, but he won’t be making art forever.

“There can be only one Richard Bresnahan. The man himself is irreplaceable,” Lemke said.

“You’ve got to think about legacy, Richard,” Bresnahan said, basically to himself. “Who’s going to take this over when you’re done?

“You don’t spend 40 years building something just to have the moment you drop over face-down into the pizza for someone to say, ‘OK, now we’re going to change everything.’ ”

At age 66, Bresnahan looks forward to that future with optimism and renewed perspective.

“Change is good in the sense that you bring in someone who has the same respect for the materials, for the creativity, for learning, for the hospitality of guests,” he said. “That will become part of the identity of the place.

“You want it to change. You have to create a certain kind of vibrancy that the next generation believes in. But the foundation will stay solid.”

Bresnahan glanced around the studio he spent 40 years building, his eyes bright.

“Your goal in life is that your apprentices become better than you,” he said. “If I can do that, then that’s the legacy.”

None of it would have happened without all those benefactors, all those pivotal moments, all those voices.

Richard Bresnahan still sees them, still feels them, still hears them. They’re waiting for him every day when he walks through those doors.