The College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University have historically had an Honors Scholars program, a destination for some of the schools’ best and brightest. You don’t get in without a high school grade-point average of at least 3.85, and each year’s cohort usually is limited to between 60 and 80 students.

But three years ago, the schools transitioned away from an eight-course ala carte approach to a distinctive set of five interdisciplinary courses. They are designed to promote a learning community in which students from all backgrounds collaborate to develop the skills to make a difference in the world.

Olivia Schleper ’23, who graduated this spring with a history degree, was one of the last to come to CSB and SJU before the change. But she joined three current seniors, who have known only the community-centered approach, to identify an opportunity to enhance the common good and present what they found in a way that could be transformational to people in Central Minnesota.

As part of an Honors 360 course (Community, Research and Social Change) taught by Brittany Merritt Nash, an assistant visiting professor of history, they posited that recent revelations of restrictive covenants in property deeds in the Twin Cities also could be found in Greater Minnesota – and likely in many places elsewhere across the country. Working with the Stearns County Recorder’s Office and the Stearns History Museum, they uncovered nearly 100 deeds that still include clauses intended to restrict the sale to and occupancy of properties from some ethnic groups. Most were in St. Cloud, but others were found in outlying areas – including the Islewood Beach section of Collegeville – just south of the Saint John’s campus.

“I’m so glad I got to do this work,” said Schleper, who is from St. Joseph, Minnesota, and expects to enroll in law school next year. “It’s sobering to see the impact of these covenants almost 100 years after they’ve been in place. It was a cool opportunity to be able to bring this to light and there are a lot of possibilities as to what happens from here.”

Though unenforceable, century-old clauses remain

With the help of a grant from the Office of Office of Undergraduate Research & Scholars that paid for access to a digital database, and many hours poring over old records, the students discerned that the oldest known racial covenant in Stearns County is from 1919. Many were created in the 1920s and ’30s and, while they became unenforceable in 1953, the language remains embedded in the deeds, and some were in sales documents signed as recent as 1981. That revelation stunned a crowd of several dozen people who packed a community room at the museum to hear about it this spring. Their work also made headlines in the media, including a story by Minnesota Public Radio.

“I had no idea about racial covenants coming into this class,” said Connor Veldman, a biology major on a pre-med track from Hollandale, Minnesota, who worked with Schleper and the others. “The research I’ve done up to now was pretty different, most of it coming in a lab setting. But I really enjoyed the social part of this project. I’m a genuinely curious person and there was a human connection to this work that I think is important in developing empathy for others.”

As has been discovered in Minneapolis, racial covenants were used to segregate communities. The patterns they created continue to exist and keep some residents from living close to parks, schools and businesses. Indeed, where you live has been proven to be a social determinant of health and longevity – which persistently varies by race.

That resonated with Robbie Smith, a biology major from South St. Paul. While he and Veldman mostly study living organisms – the kind you can find under a microscope – the history project broadened their worldview and gave them a chance to bring a scientific approach to the group.

“I never thought there would be this much interest in what we were doing, and that makes me really happy to have been a part of it,” Smith said after a slideshow presentation lasted nearly an hour – including questions that eventually had to be cut off for time. “We are going to continue to work on this in the fall and hopefully the project is going to live beyond our time at Saint Ben’s and Saint John’s. It would be great for others to get a chance to participate in this – whether you’re an honors student or whether it’s an elective. It’s important for the community to know this stuff and there’s so much more research that can be done. Hopefully, other people will want to step in and give us a hand.”

Eileen Otto, a political science major on a pre-law track from Delano, Minnesota, rounded out the group of four. She said the honors framework provides exposure to other disciplines some students might not otherwise experience.

“One of the classes focused on gender and math,” Otto said. “I’d never taken any math classes here because they weren’t part of my major. But there I was one of about 12 students getting exposed to numbers theory. I spent a lot of time looking at the board going ‘Huh?’ But eventually it started to make sense, and I learned a different way of thinking.”

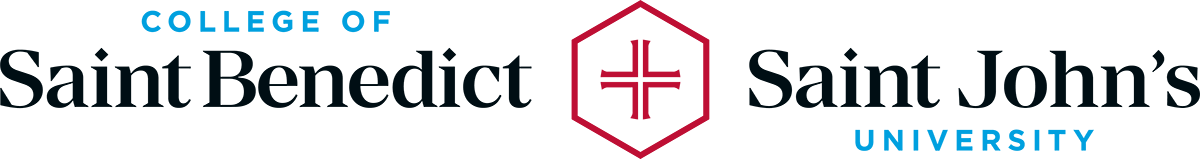

Olivia Schleper (left) and Eileen Otto speak about an example of a property deed from Stearns County that contains racial language.

Honors curriculum fosters collaborative leaders

The Honors Scholars curriculum begins with Honors 120 (Community and Identity) for first-year students. They explore why gender, race or ethnicity – in isolation – is insufficient to conceptualize either individual or social identity. They learn to think critically about their own identity and the factors that contribute to those generalized for gender, race and ethnicity. Then they contemplate how those affect power and justice in the contemporary United States. Finally, they are introduced to the value-based, collaborative theory of leadership that is central to the other courses.

Sophomores explore Interdisciplinary Approaches to Communities of Scholarship (Honors 201-204), which engages the foundation of a liberal arts education – to acquire knowledge broadly and across different domains for the importance of valuing multiple perspectives en route to framing a belief or making a decision. These courses are all team-taught by professors from different disciplines.

Additionally, during their sophomore year students study Communities and Systems (Honors 300). This addresses how race, gender and ethnicity shape cultural rules and biases across time and in different societies.

All Honors Scholars will engage in the Community, Research and Social Change class as juniors, and follow that with Honors 395 (Liberal Arts in Action) as seniors. This final capstone course integrates their previous work into a project that enhances the common good of the community. Schleper, Veldman, Smith and Otto already have developed a plan to create an exhibit at the Stearns History Museum as well as produce an article for its quarterly magazine Crossings.

“Our Honors Scholars put their academic knowledge into action in community-engaged projects that address real-world challenges,” said Beth Wengler, a professor of history and director of the Honors Scholars program at CSB and SJU. “The program prepares students from all different majors to collaborate on this work. In small discussion-based courses, they wrestle with universal questions about the human condition in light of the particular challenges of the 21st century. As juniors and seniors, they partner with local organizations to design and implement projects that serve the common good of the community. And that provides the foundation for them to create meaningful and positive social change as professionals and leaders in their communities for the rest of their lives.”

Projects of many scopes build on coursework, research

The research into racial covenants is just one of many projects under the direction of Brittany Merritt Nash, visiting assistant professor of history, and Sucharita Mukherjee, professor of economics, who led the junior-level courses this year. Others included a historical look at sexism on campus, research into conflict between the Catholic Church and the LGBTQ+ community, exploration of the Chinese international student experience at CSB and SJU, and additional collaborations with Habitat for Humanity, Anna Marie’s Alliance and the Boys and Girls Club of Central Minnesota.

Perhaps none generated buzz like Schleper and her peers, however. The students hope their efforts will spur a drive, at least symbolic in nature, for property owners to strike the racial covenant clauses from their deeds. Stearns County Recorder Rita Lodermeier, who attended the group’s presentation at the museum, said she has reached out to the Just Deeds coalition, which already has begun the process in nearly two dozen other Minnesota cities.

Otto, Veldman and Smith will continue their research in the fall, and Schleper intends to maintain contact with the team as it continues studying racial divides in real estate.

“The Honors experience was great,” Schleper said. “You’re in a group of motivated students who want to be there and are vested in what we were doing. We spent a lot of time on this project – more than you could say was required for class – but it was fascinating. We learned things we never knew and brought attention to something many people didn’t know about. I think I’ll remember this experience the rest of my life.”

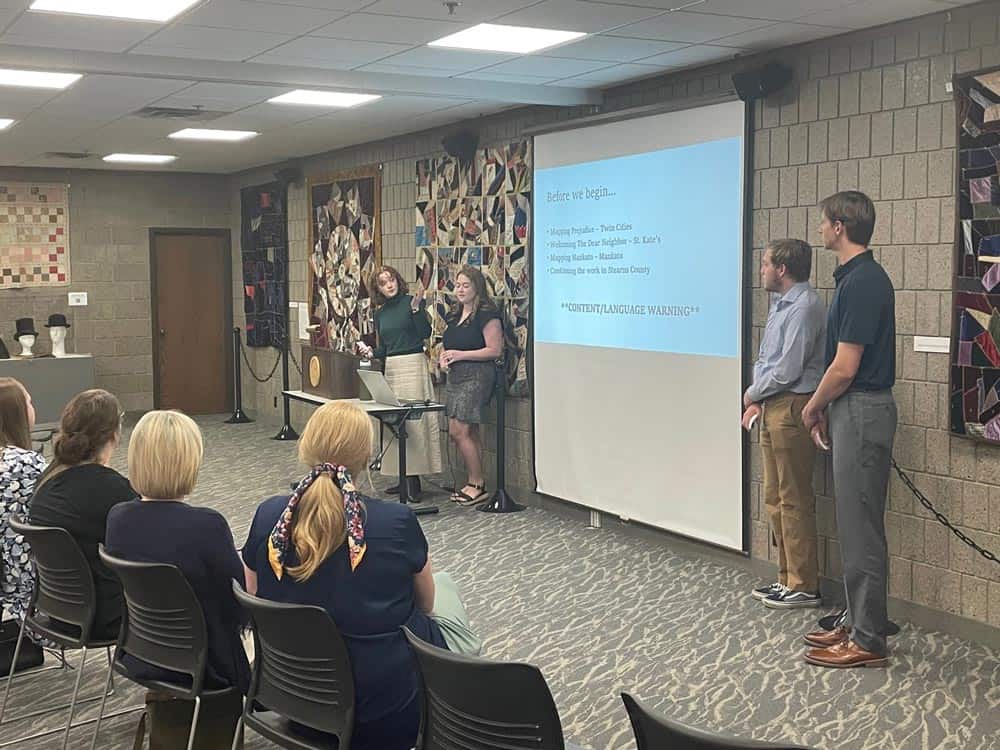

Olivia Schleper (left) and Eileen Otto begin their presentation before a crowd of interested citizens on May 17 at the Stearns History Museum. Robbie Smith and Connor Veldman are at right.

Olivia Schleper (left) and Eileen Otto begin their presentation before a crowd of interested citizens on May 17 at the Stearns History Museum. Robbie Smith and Connor Veldman are at right.

Brittany Merritt Nash, a visiting assistant professor of history at the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University, congratulates four of her Honors Scholars students following a presentation on their investigation of racial covenant data on May 17 at the Stearns History Museum. The students include (from left) Connor Veldman, Robbie Smith, Olivia Schleper and Eileen Otto. At right are Cortez Riley, equity and inclusion partner with Stearns County, and Rita Lodermeier, recorder for Stearns County. The group uncovered almost 100 deeds in the area that contain racial restrictions on their sale or use. Though the covenants have been unenforceable for more than 60 years, their impact continues to be evident in current society and CSB and SJU hope to continue the research in the years to come.